Please visit the Tibetan Feminist Collective (TFC) at our new website!

Good Tibetan Women

By Kaysang

I have heard countless Tibetan men say that there isn’t really anything for Tibetan women to complain about in terms of gender equality because we Tibetan women “have it so much better than women from other communities,” to paraphrase the general lines. The usual example cited by Tibetan men is how women in India are often beaten and burnt alive for not paying dowry but that in the Tibetan community there are women who beat their husbands. When did Tibetan men stoop low enough to compare themselves to systems which inflict such injustices upon women?

In our society, Tibetan women are still expected to be docile, obedient, “good” mother/daughter figures, usually defined by the kind of clothes we wear, the degree of servility and acquiescence we show towards elders, readiness to agree with the men in control, lack of any inclination to argue, and being expected to want to settle down and marry. A vast number of women may be running everything in their households and society, from domestic duties to family businesses to being political leaders, but to be a truly “good Tibetan woman” one is expected to be “obedient” and be good wives/mothers/daughters (which, more often than not, entails surrendering to men).

Tibetan women are raised hearing things like “but you are a girl”, “this isn’t what good bhoepa girls do”, “this is what good bhoepa girls do”. I agree that there are many safety concerns as women living in India, but why should boys get to do anything while girls are always warned to keep in mind their gender? As if our gender is a limitation.

When I point out this double standard people will often reply, “Oh, but men and women are equal so you can do whatever you want.” But they will then try to put a leash on their own wives, sisters, daughters, nieces, and cousins. In India, women need to develop heightened levels of consciousness about safety in order to avoid dangerous situations. However, rather than focusing entirely on restricting freedom of movement and choice for women in the name of safety, people should be focusing on the primary cause of the problem: Men’s attitudes towards women. We are raised with the belief that Tibetans are compassionate, forward-thinking and open minded, but we always manage to categorize women into either the “good” or the “bad” ones (and we all know the standards by which goodness is measured).

For example, in Dharamsala, married women who do not like wearing chupa usually are looked at differently. The chupa has almost become the yardstick by which to measure the respectability of a woman. We live in families where women are still expected to do all the household chores even if they work the same kinds of 9-5 jobs as their husbands. Yet, men aren’t expected to handle anything in the kitchen – even when they know how to cook – while the women cannot even have control over whether or not to wear chupa, constantly having to be conscious of what our society will think. Men never have to worry about wearing chupa, except on very rare occasions. If a woman likes wearing chupa and is by nature quiet and doesn’t like confrontation, then that is her choice. But why should the women who are not like that be treated any differently?

Why is it not okay for a bhoepa girl living in India to wear revealing clothes and makeup but a girl from chigyal doing the same is still considered a “good girl” simply “because she’s from the US/Canada/Switzerland/insert western country here”? My friends who have come on vacation to India after some years abroad can wear tank tops or shorts in McLeod Ganj and the elders will let it slide because “she is from chigyal.” But the dress code imposed on local girls is always pants and t-shirt or chupa.

Why should only the wife cook dinner and wash dishes while the husband watches TV or catches up on some paperwork from the office? Why are daughters raised never to question and always to “listen to your elders” (even if the elders in question are wrong), to not fight for themselves (“good girls don’t fight”), to “accept their fate” and sacrifice all the time (because “that’s what Tibetan women do”)?

Men might say that we, Tibetan women, have it “better” than women in other communities. But “better” is not good enough.

Tibetan Feminism: Building Strength Within The Community

By Dolma*

When we discuss progress for Tibetans, we often do so in regard to relations with China, or relations with the West, placing the focus outside the community. What I hope to relay with this piece is the importance of turning our gaze within the community, towards improving the relations we have with each other. This is in the best interest of every Tibetan individual, as well as for the various causes we fight for because there is no doubt that a unified community is both stronger and more efficient.

There are a lot of heated feelings around the word “feminism.” It’s both a taboo word and a buzzword. People sometimes fear feminism, thinking it’s an aggressive tactic to instill women’s superiority that creates more hatred towards men rather than truly aiming towards harmony. When used as a buzzword, we often label anything even remotely related to women’s empowerment as feminism. The danger of this usage is that we risk oversimplifying our current social dynamics. We reduce the meaning of feminism so that we look at only gender on a one-dimensional plane, when in actuality, so many other factors such as race, sexuality, and citizenship also intersect to shape identities in very different ways. These factors are all interconnected and cannot be examined separately from each other. This is the basic idea behind intersectional feminism.

Mainstream (White) Feminism

Feminist movements are generally co-opted by cisgendered white women preaching about sexual liberation and wage equality, blurting out facts about how women make 78 cents to a man’s dollar when actually, that statistic applies only to white women. Black women and Latina women make a fraction of the salary that white women make, yet this fact frequently goes unacknowledged. Mainstream white feminists can even be heard complaining that people of color and LGBTQ+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer) communities aren’t “rising” and “uniting” together for women, downplaying the significant role that white women historically have had in ignoring and marginalizing these communities in pursuit of their own agendas.

They demand representation, but are satisfied when the representation only extends to white women. They highlight issues that specifically include them over life-threatening issues faced by others, such as the incarceration of transwomen of color, or immigrant women being forced into unsafe working conditions and experiencing higher rates of domestic violence. Thus, when we glance at the forefront of feminism, at the popular mainstream issues, it can be easy to dismiss it as something not relevant towards Tibetans. And this is why it was so significant for me to be introduced to intersectional feminism, not because I now understand every culture’s struggle (I don’t), but because I now realize that feminism encompasses numerous layers and dimensions of the many times, places, and cultures; meaning that it is also something for Tibetans.

Feminism is Equality

Since equality looks different across different cultures and spaces, we must be conscious of the politics of each community. Reaching for equality includes breaking the various forms of oppression within our own communities.

Having grown up with Tibetan parents, it hasn’t been hard to see the significance of gender roles. Whenever we have guests, my pala (“father”) will take a seat in front of the window with an alcoholic beverage in one hand while he fills the room with his boisterous voice. Meanwhile, my amala (“mother”) is in constant motion providing snacks, pouring drinks, cooking dinner, and keeping the place tidy. This is just my role, she’ll say with an unquestioning tone of acceptance.

She often tells me about how she got lucky with my father and their arranged marriage, recalling the many women who end up with selfish, lazy, and even abusive husbands, who remain in the marriage because of children and the stigma of divorce.

My pala is a good man, but when he gets drunk, his anger and nonsensical ramblings are always aimed at amala. I once was in the middle of a loud dispute, trying to question him about his continuous habit of drinking, to which he kept (drunkenly) responding that I, as a woman, simply could not understand.

My pala is a well-respected man and takes good care of the family, yet there is some underlying force that normalizes the act of a man assuming a subconscious sense of dominance over the woman, and of a woman being expected to endure and carry on. This is called patriarchy.

The point here is not to shame the homemaker’s role, but rather, recognize that this role, as well as every other role, should be one’s own choice.

Sexuality: Taboo in Tibetan Communities

Another impact of gender roles includes the stringent monitoring of sexuality. Who knows what young men do after they walk out the door? Yet, giant waves of gossip and hell break loose when a woman is even thought to be engaging in “dirty” fun.

Of course, I won’t mention sexuality without also acknowledging the heteronormativity of Tibetan communities. We raise our daughters to be with men and vice-versa. I can’t speak thoroughly on the different sentiments towards homosexuality, simply because it’s hardly acknowledged within the Tibetan communities.

Once, I asked my amala what would happen if I were to be openly involved with another woman. She said that although she may eventually accept it, it would be a very big problem for my pala. Unsurprisingly, the most importance is given to the impact on the man in this situation. She said the public gossip and shame would cause a lot of distress to him, which also implicates the community’s sentiments towards homosexuality. There is also a tendency to assume a person’s queerness (a term that describes a range of non-heteronormative, non-cisgender identities) is an attempt at being white, a modern inji notion, which further invalidates and erases real identities.

Topics about gender and sexuality are too often treated as taboo and pushed to the margins of the Tibetan movement. Many of us will throw a word of support to gender issues or gay rights movements that are seen in the media, however, we treat them differently when they concern our actual community. Issues such as gender based violence are threatening people’s safety right now. I have had multiple experiences where a Tibetan couple or family is brought up in conversation, and someone will casually tell me that the husband is known to be physically or verbally abusive to his wife.

Casually, as if a person’s suffering can be dismissed as normal gossip.

Casually, as if my horror at the story is an overreaction.

Casually, as if this is an isolated situation rather than an outcome of a continuing system of patriarchy.

How do we, as a community, effectively come together for a cause when we ignore and perpetuate violence against our own members? How are we expected to unite when our community members feel silenced in their own spaces?

Why I Believe in Tibetan Feminism

Tibetan feminism is a movement to create a community welcoming and inclusive of people of all sexualities, all genders (women, trans, non-binary, genderfluid, etc.), all abilities (mental, emotional, physical), all skin shades, all body shapes, all experiences, and all the other identities that are marginalized and silenced by our communities.

However, this unification comes with the deconstruction and derailment of our own privileges (such as being a man, being straight, being financially stable, etc.) because the agency taken away from some is a given source of power and privilege for the rest of us. So, unless we are willing to bring ourselves into this struggle, actively and consistently working to dismantle oppressive power structures no matter how deeply rooted in our lives they may be, we are complicit in the further suffering of our community.

Sometimes the argument of culture is brought up, suggesting that change is a threat to cultural preservation. However, if oppression is tied into certain cultural practices, then there is still no justification to supporting that oppression. Change must happen, but change does not have to be a rejection of our culture. We can celebrate our culture, while also making improvements to avoid hurting others.

The Tibetan feminist movement includes listening to more of the narratives of women and other marginalized identities in the Tibetan diaspora, encouraging critical thinking among our youth, and engaging in topics that may not be comfortable for some, but are vital for this community to heal and grow together. This will allow Tibetans to have agency over our own minds and bodies and develop a community that is open and receptive to all.

To conclude, I see Tibetan feminism as a positive force that can allow us to create a truly loving and compassionate community, deriving strength and resistance through cooperation and unity. By working with each other and for each other, we will be able to construct a better present and future for all Tibetans.

*Names have been changed to protect the author’s identity

ཕྱུ་པའི་འཆིང་སྒྲོག་ལས་གྲོལ་བ།

aaa

ཕྱུ་པའི་འཆིང་སྒྲོག་ལས་གྲོལ་བ།

aaa

༼བོད་ཀྱི་སྲོལ་རྒྱུན་དང་རིག་གཞུང་རྒྱུད་འཛིན་དེ་བོད་ཀྱི་བུད་མེད་ལ་བཀལ་བའི་ངན་ཁག༽

aaa

ཡེ་ཤེས་སྒྲོལ་དཀར།

ང་རང་ཉིད་ཀྱི་ཕྱུ་པར་དགའ།

དེའི་མཛེས་པ་དང་ཉམས། བདེ་བ་བཅས་ནི།

རྡ་སའི་གཞུང་ངམ་ལྷ་སའི་ཁྲོམ་གྱི་གྲང་ངར་ལ་རན།

ང་རང་ཉིད་ཀྱི་ཕྱུ་པར་དགའ།

ང་ལ་དེ་བདག་གཅེས་བྱེད་དུ་འཇུག་རོགས།

དུས་ནམ་ཞིག་ཏུའང་།

གནས་གང་ཞིག་ཏུའང་།

ང་རང་ཕྱུ་པ་དང་མཉམ་དུ་རང་དབང་གྱི་གར་ལ་རོལ་དུ་འཇུག་པར་ཞུ།

aaaaa

ང་ལ་ཕྱུ་པ་བཙན་དབང་གིས་མ་གཡོགས་རོགས།

དེ་ལྟར་བྱས་ཚེ།

ཕྱུ་བ་ནི་བཙིར་ཡོང་བའི་འཆིང་ཞགས་ཞིག།

བསྡམ་ཡོང་བའི་འཆིང་སྒྲོག་ཅིག།

དབུགས་བསྡམས་པའི་བཙོན་ཁང་ཞིག།

ང་ཡི་ཕྱུ་པ་གཉའ་གནོན་གྱི་རོ་རས་མ་བསྒྱུར་རོགས།

ང་རང་ཕྱུ་པ་དང་མཉམ་དུ་རང་དབང་གི་གར་ལ་རོལ་དུ་འཇུག་པར་ཞུ།

aaa

ང་རང་ཕྱུ་པ་དང་མཉམ་དུ། བྱ་ལྟར་རང་དབང་གིས།

ནམ་མཁའི་མཐོངས་ནས་མཐོངས་སུ་འཕུར་ཆོག་པར་ཞུ།

ང་རང་ཕྱུ་པ་དང་མཉམ་དུ། ཉ་མོ་ལྟར་རང་དབང་གིས།

མཚོ་མོའི་གཏིང་ནས་གཏིང་དུ་འཛུལ་ཆོག་པར་ཞུ།

ང་རང་ཕྱུ་པ་དང་མཉམ་དུ། རྟ་ཕོ་ལྟར་རང་དབང་གིས།

རྒྱ་ཆེ་བའི་རྩྭ་ཐང་བརྒལ་ཆོག་པར་ཞུ།

ཡིན་ནའང་། ཕྱུ་པས་ང་རང་བསྡམ་དུ་མ་འཇུག་རོགས།

ང་རང་ཕྱུ་པ་དང་མཉམ་དུ་རང་དབང་གི་གར་ལ་རོལ་དུ་འཇུག་པར་ཞུ།

Let Me Dance With It In Freedom !

(The irony of preserving Tibetan tradition and culture by imposing it on Tibetan women!)

By Yeshi Dolkar

I love my Chupa¹;

Its elegance, dignity, comfort.

A wise wear for the cold of Lhasa² or Dhasa³.

I love my Chupa;

Pray! Let me cherish it

Wherever, whenever;

Let me dance with it in freedom!

Do not impose it on me;

For then it’s a noose –constricting!

A shackle- restricting!

A prison – stifling!

Pray! Do not make my Chupa

A shroud of oppression;

Let me dance with it in freedom!

Let me soar with it, free like a bird

High, high into the sky;

Let me dive with it, free like a fish

Deep, deep, into the sea;

Let me run with it, free like a horse

Far, far, across the moor;

But pray! Do not bind me with it!

Let me dance with it in freedom!

¹ The traditional dress worn by Tibetan women

² The capital city of Tibet

³ The short form of Dharamsala – a small town in Northern India where His Holiness the Dalai Lama is seated in exile

Author Bio: Yeshi Dolkar graduated from the Tibetan Children’s Village (TCV) school in Dharamsala, India and later obtained a college degree in Education. After working as an English and Economics teacher at TCV for 30 years, she later joined the Dalai Lama Institute for Higher Education in Bangalore (an undertaking of TCV organization). She has been working as a lecturer there for the past five years training primary school teachers in English as a foreign language.

Thoughts on Tibetan Feminism

By Migmar Dolma

Women are oppressed or neglected all over the world to this day. Patriarchy is human made. It is not inherent in mankind. We as individuals interact with each other through social relations in which we produced and are reproducing the belief that gender roles are legitimate because they are nature-given. If we created a patriarchal system we can also dismantle it to build a gender equal society. Norms and values are defined by us as members of society. We have the power to change them.

Since this is my first written piece on Tibetan women I want to dedicate it to my Amala who has always been a role model to me. She taught me and my sister to truly be ourselves when she herself grew up in an environment where she couldn’t fulfill herself. Her story and her experiences are undeniably part of why I care about Tibetan women’s equality and rights.

Tibetan Women – Silenced Twice

Today Tibetans are silenced. Tibetans are not equal citizens of this world because our territory is under control of the Chinese Communist Party and therefore occupied by a foreign country. Inside Tibet, Tibetans are being silenced because of the ongoing colonization of Tibet and Tibetans’ lives. As for Tibetans living in exile, we feel as if we do not fully belong to the countries we live in. The exile situation leads us to feelings of unconscious inferiority or alienation as a society. This is also partially the reason why we still long for our homeland Tibet and have a strong sense of “long-distance nationalism”(1) towards a country that many of us are not even allowed to visit.

Women’s narratives have been and still are neglected by society to this day. The main point of view is always that of a man. So, in a sense, Tibetan women are being silenced twice as much as men. We are silenced and oppressed as a nation but we are also looked down upon and discriminated as women in our own communities.

When I talk about discrimination, I don’t mean institutional discrimination in the sense of discriminatory laws, such as when women didn’t have the right to vote or to have bank accounts in their names. The discrimination that I speak of still persists in our society today in the way we talk about, define, and judge women in our everyday lives.

Bhumo vs. Bhu : Double-Standards

When Tibetan parents tell their daughters not to go out at night and not to date boys, they are imposing double standards. Do they apply these same rules to boys? No. In fact, stereotypes and idealized images of what a woman ought to be is not protecting or benefitting women – on the contrary – it puts women in a position where they are less likely to live their lives in full freedom and as equal human beings in our society.

I recall an experience I had in Ladakh that demonstrates this point. I was outside a little restaurant in Choglamsar smoking a cigarette one day. A young Tibetan man was also smoking a cigarette and observed me for a few minutes before approaching me, telling me to “Be aware! There’s an association called ‘Ama Tsokpa’ (Mother’s organization). They can be very aggressive and might call you out when they see you smoking on the streets”. Now just to be clear, I do not and would never encourage smoking to anyone. It is a bad habit of mine which I admit.

But why does it make a difference whether a man or a woman smokes? Why do we set standards for women that are not applied equally to men in our community? Why do I need to feel bad when I smoke in public, whereas a man can smoke freely without shame or judgment? Although some readers may think that I exaggerate, this is just an example that shows how deeply-rooted gender inequality is in our own day-to-day life. It is these little and seemingly trivial patterns which cumulatively add up to limit Tibetan women’s agency both in public and in private.

It is also proof that we as Tibetan women are part of the problem. ‘Ama Tsokpa’ as the name tells us is a women’s organization. We need to free ourselves from these images of ourselves as women that we, too, reproduce.

Women of the Snow Land: Two Freedom Movements

I don’t know much about feminism inside Tibet since most of their writings are in Tibetan and therefore inaccessible to me as of now. But from some friends who’ve grown up inside Tibet I know that women’s situation in Tibet is extremely difficult and heartbreaking. On the one hand because of Chinese oppression which women suffer from equally to their countrymen. It is a fact that forced sterilization is a brutal violation of a woman’s self-determination over her own body. On the other hand there are ill-treatments of women which still occur within Tibetan communities: Domestic and sexual violence, health problems (AIDS for instance), fewer opportunities for schooling and hard labor. In 2008 Jamyang Kyi, a Xining based writer and most known Tibetan feminist said to L’OBS, a French newspaper:

“They [women] are doing 70% of the work. I’m not talking about household or the upbringing of children which they assume to 100%. I’m talking about the field work of farmer women, the maintenance of herds for nomadic women. They’re doing 70% of it. And nevertheless they are completely subordinated to men, much less free and much less educated than men are.” (Original in French)

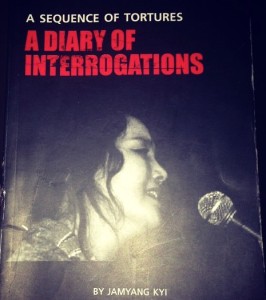

When I first came across Jamyang Kyi it blew my mind. I felt pride in being a Tibetan woman because for the first time I heard the voice of a Tibetan woman so loud and clear. I read “A Sequence of Tortures: A Diary of Interrogations” (original in Tibetan: མནར་གཅོད་ཀྱི་གོ་རིམ།) that the Tibetan Women’s Association published as a book and translated into various languages (like English) and which was given to me by Dhardon Sharling, Member of Tibetan Parliament in Exile, when she visited Switzerland last year. It is a diary written during her detention in 2008. The detailed account of what imprisonment and interrogations felt like to her is so direct and intimate that it moved me deeply. She doesn’t portray herself as a hero but rather describes her fears and doubts that she goes through with honesty. But for me she indeed is not only a hero but a revolutionary because she did not only selflessly stand up for the Tibetan people but she also dares to criticize conservative thinking and discrimination towards women in her writings. A friend of mine from Amdo told me that high lamas and monks abused her verbally when they didn’t agree on her opinion saying she is a prostitute who sleeps with many men. Do you think these humiliating words would have been uttered if she was a man? No, me neither! But she doesn’t give up despite Chinese intimidation or these ugly attacks from conservative Tibetan men. This is why she symbolises women’s resilience and courage to me.

that the Tibetan Women’s Association published as a book and translated into various languages (like English) and which was given to me by Dhardon Sharling, Member of Tibetan Parliament in Exile, when she visited Switzerland last year. It is a diary written during her detention in 2008. The detailed account of what imprisonment and interrogations felt like to her is so direct and intimate that it moved me deeply. She doesn’t portray herself as a hero but rather describes her fears and doubts that she goes through with honesty. But for me she indeed is not only a hero but a revolutionary because she did not only selflessly stand up for the Tibetan people but she also dares to criticize conservative thinking and discrimination towards women in her writings. A friend of mine from Amdo told me that high lamas and monks abused her verbally when they didn’t agree on her opinion saying she is a prostitute who sleeps with many men. Do you think these humiliating words would have been uttered if she was a man? No, me neither! But she doesn’t give up despite Chinese intimidation or these ugly attacks from conservative Tibetan men. This is why she symbolises women’s resilience and courage to me.

As I heard from different accounts of my friends, the situation of Tibetan women in rural areas still remains very harsh and discrimination against women persists there to the extent that they are not even regarded as human beings. Apparently in some rural nomadic areas there are these derogatory terms used by men for women like: ནག་ཆགས། meaning the ‘black one’ or ‘the dark one’. But it seems that in bigger villages or cities women’s situation is improving. I recently talked to someone from Tibet who told me that women are starting to get together and discuss women’s issues. He visited an annual women’s rights conference three times. At the first conference he said, women didn’t dare to speak and instead let the male monks speak whom they had invited. Then gradually it became better and at the last conference which took place around 2010 all women expressed their thoughts with self-confidence. This is definitely a good development and very inspiring when one recalls that these women live under Chinese authoritarian rule where Tibetan civil society is heavily controlled.

Rangzen and Feminism: Incompatible?

Some of my male friends tell me half-jokingly: ‘Just put this women’s movement thing aside for a moment. Let us first have independence and freedom for Tibet!’. But I wouldn’t separate feminism from Tibetan independence. Why? If a woman can’t stand up for herself, she won’t stand up for her nation. If our society succeeds to encourage women to their full abilities we will see women being able to lead a self-determined life, free from social pressure. Summed up: If women do well, our nation will do well.

Sometimes we – Tibetans in Exile – look at ourselves as victims which is partially also due to the mainstream image which is imposed on us by the West. But we are not victims. Tibetans inside Tibet are not victims. Tibetan women are not victims. It is resistance which defines us not a passive victim’s role. Even with continued Chinese occupation and unjust policies we continue to exist – either in Tibet or in Exile. We continue to live and define ourselves according to time and place. This is why I believe in freedom and gender equality because I believe in Tibetans’ courage to change and to move forward. We will move forward to a time where Chinese occupation will be a past chapter of our history. What is Tibet going to be? I personally imagine a future Tibet like this: A country free from foreign occupation and Tibetans living in a free and democratic society where women are respected and regarded as equals. I hope that it will become a part of what our collective free Tibet will be.

(1) Fouron, G., & Schiller, N. G. (2001). All in the Family : Gender, Transnational Migration, and the Nation- State. Identities : Global Studies in Culture and Power, 7(4), p. 542.

Published on the Tibetan Political Review!

Thank you to our friends at the Tibetan Political Review (TPR) for publishing our post! Here’s the link to awesome TFC Contributor Tsechi Chuzom’s “A Tibetan Feminist’s Response to Adele Wilde-Blavatsky” on TPR’s website.

Here’s to the glorious first amendment!

-TFC

A Tibetan Feminist’s Response to Adele Wilde-Blavatsky

By Tsechi Chuzom

According to this “author,” I, Tsechi Chuzom, child of Tibetan refugees who fled Tibet during the communist Chinese invasion, president/board member of SFT MHC & Lakeside for multiple years, cannot “understand” or “speak on the behalf of Tibetans in Tibet” (don’t worry, I’ve been there and still don’t claim to do so). But somehow she, Adele Wilde-Blavatsky, whiter than crack,* has the moral and cultural authority to say that we in the US Tibet movement advocate “a particular pseudo-intellectual, Occidentalist, hyper-nationalist brand of identity politics” that is bad for Tibetans in Tibet.

I know this is just an insecure troll, and I don’t like dignifying her accusations and embittered rants with a response, but I also cringe at the thought that others might read this or her other “writings” on Tibetan culture and society, thinking it is an accurate or fair portrayal of the Tibetan diaspora.

She holds onto the notion that living in Dharamsala and choosing to study Tibetan Buddhism and language gives her credibility in determining all things Tibetan. What she fails to understand is that whether or not I identify as Tibetan isn’t so clear a choice for me as it is for her. It’s very easy to sit back and criticize a community to which you are not fundamentally attached. Unlike her, I don’t have the privilege of deciding one day that I don’t want to care about Tibetan issues anymore because they are not necessarily mine to care about. Being Tibetan is a fundamental part of who I am. When there is criticism, I and my fellow Tibetans bear the burden of resolving those issues; she chooses whether to be affected or offended by it or not. Being a self-proclaimed “Tibet supporter” does not automatically give you the cultural context and authority to constructively– and respectfully– criticize our community and cultural heritage.

God forbid the Tibetan community make any mistakes. In her article, she argues that any Tibetan who does not “present a Shangri-la version of Tibetan society… is demonised and isolated.” Yet, she seems to hold us to that very same impossible Shangri-la standard that she is so eager to denounce. Of course Tibetans are going to be hostile when an outsider is speaking half-truths and taking a verbal dump on our culture. While I admit Tibetans, especially our elders, are fairly conservative and unresponsive to criticism, this is an understandable result of losing one’s own country and having one’s traditions completely ripped apart.

What we Tibetans are witnessing is the active cultural desecration and dilution of our ancestral homeland and way of life. It is comprehensible that some hold onto the very justified fear of cultural extinction, which may translate into what is perceived to be a certain strain of xenophobia and/or conservatism. I am not saying this is okay, but at the same time, this reaction is not unique to Tibetan society. Are we not allowed to work within our own community to resolve our issues on our own terms?

I don’t claim to have a clearcut solution. All I know is, I will not chastise nor distance myself from my community simply because certain aspects are seemingly flawed or imperfect; I will recognize the responsibility and privilege I have as a Tibetan to try to work through these issues for the greater good of our people. And most importantly, I will always choose to be a positive force in whatever I endeavor.

*Is crack even white? No disrespect to white people– much love to my white friends!

Mother & Child

By Tashi Dekyid

I am not sure how western feminists interpret the relationship between women and children. In my experience working with Tibetan grassroots organizations in eastern/northern Tibet, when we talk about women’s issues such as health and education, mother and children are typically brought together.

For example, many people advocate the importance of education. Women’s education is particularly prioritized because they are considered to be the ones who will have the most critical role in educating the youth. The education of the future generation of Tibetans is thus considered to rely upon one’s mother.

What Does Tibetan Feminism Mean To You?

TFC is actively seeking submissions in response to the following question:

“What does Tibetan feminism mean to you?”

Please note that there is no word limit for response pieces. We accept submissions either anonymously or under a name/pseudonym, so please let us know if/how you’d like to be credited when you submit your piece.

Thank you, and stay tuned!

-TFC